Today I had the opportunity to see some of the prominent works from renowned French Sculptor Auguste Rodin at Musée d’Orsay (the plaster model from 1917). One that stuck with me is called “The Gates of Hell” :The actual size of it, the amount of figures, the concepts of it covers and the story behind it. Especially its story: I’ve found some inspiration to keep writing and learning “hard” things.

I’ve known Rodin’s The Thinker since my childhood. A larger replica was a central figure in one of the well-known mental health hospitals in my home city. I remember how impressed I was as a child: This deep thinking man seemed like a embodied form of the hospital’s soul with its thoughtful posture combined with sorrow. It’s still difficult to imagine for me how to carve this depth of humanness out of a physical material like bronze, stone or something similar…

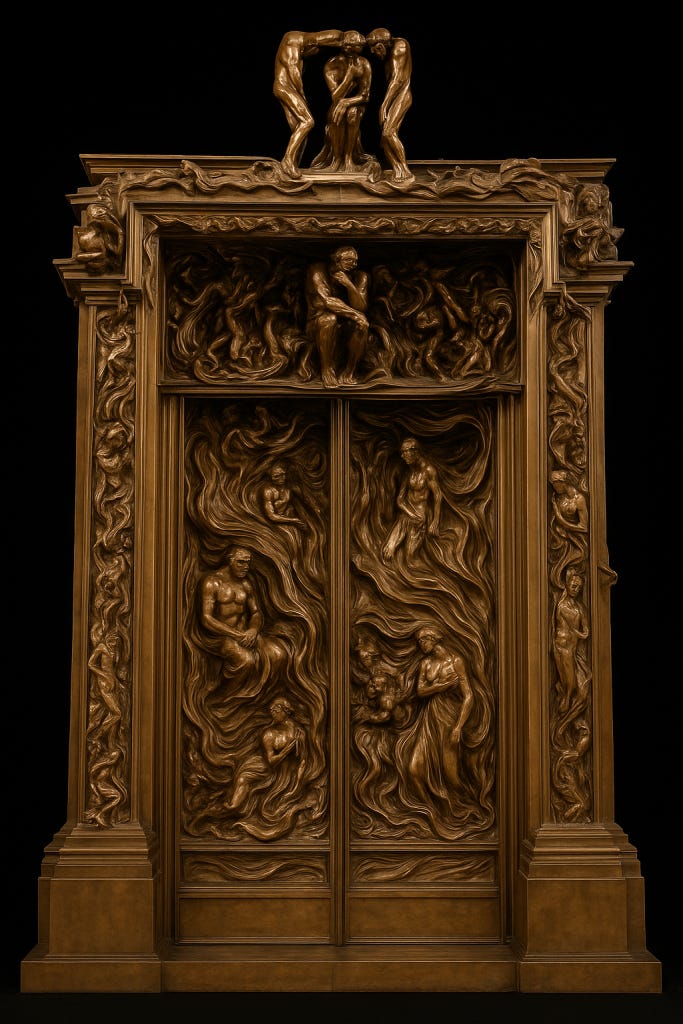

Yesterday, I learned that The Thinker was originally a part of The Gates of Hell; looking down what’s happening from top… In 1880, Rodin was commissioned to create Gates of Hell, inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy, for the planned Decorative Arts Museum. In fact, The Thinker there was Dante himself from Rodin’s eyes. The doors are looking like flames or ocean waves in motion, where figures of various sorrow and pain appear at a glimpse, waiting to disappear in moments again. This capacity to reflect motion in sculpting was new and original at the time, the experts say. Rodin, according to them, managed to combine the classical influences like Michelangelo with these new interpretations. What’s stunning about these figures, covering all facades of the Gates represent different forms of human suffering, Ugolino eating his own children, a female figurine harrassed by a demon, a face of sorrow. Some of Rodin’s well-known sculptures, The Thinker, Fugit Amor, Ugolino and The Kiss (the doomed lovers from Dante’s work), are actually the larger versions of what’s on The Gates. In a way, this masterpiece is also a guide for Rodin’s wonderful work.

And, the story gets more interesting. The French government withdrew the commission after three years. But Rodin decides to continue working on it because he finds his tone, his muse in there, I assume. He spent the last 37 years of his life with it but couldn’t finish. No one knows what it would look like at the end but it’s up for our imagination. This is what ChatGPT thinks and also here’s some more art history on this topic.

Now, I want to take you somewhere else – to the moment where Rodin heard about losing the funds. Speculating here. Perhaps he was surprised or may be he was expecting this. He could have thought of two things: (1) I’ve already invested in this too much, (2) I’m in depth of it and want to follow it until emerges. I don’t know but I want to believe the second option.

On another level, I’ve experiencing a similar with deep tech. The more I learn and create things with emerging technologies, I get curious, humbled and sometimes frustrated with it… Failure and success of my code, trouble of understanding the errors and the joy of seeing working code. The continious interaction, the practice, makes me know about myself and the work. In other words, the things I shape whether it’s code, text or anything else, also shape me as their creator.

I’ve been writing for a while now, and my writing revolves around learning, technology and personal discoveries around them. As I write more about these half-baked, curiosity-driven ideas, I’ve found that I get more interested in what’s happening around me and what I am learning from it. The simple act of writing had a secondary effect of organizing my thoughts. And, this organization leads to reflection and learning. In simple terms, the practice begets reflection and learning. On a third level of impact, life has become a deeper container of curiosity. And, in return, I get to bring more of my voice, thoughts and learnings into my writing. I started to recognize what’s not easily identifiable before.

Perhaps, Rodin noticed something similar: He saw that the more he works on his masterpiece, it also works on him. When he lost the commission, he did not mind because he was already onto something more meaningful for him. Then, he decided to expand it out and produced some of his most wonderful work through it.I can’t know what Rodin truly felt, but I like to imagine he saw what I see: that the work we create also creates us.

I wonder what is something you practice, at times it feels difficult, meaningless and irrelevant but deep down you know you are onto something? In other words, what’s your version of The Gates of Hell?